|

Paphiopedilum, Phragmipedium,

Cypripedium, and Mexipedium

Text and Photos by Marianna Max

Even for people who have gained experience

pollinating other orchid genera, Paphiopedilum and

Phragmipedium pollination can be quite mystifying at

first glance. For those used to seeing a small sticky stigma

that seems to "grab" the pollen, the broad smooth stigma

found in Paphiopedilum and Phragmipedium can

seem quite foreign. Pollination of the subfamily

Cypripedioideae (Paphiopedilum, Phragmipedium,

Cypripedium, Mexipedium) is in fact quite easily

accomplished once all of the "parts" are recognized. For

that reason we will start with an anatomy lesson and

dissection of a typical Paphiopedilum flower.

Figure 1 shows the front view of an intact

Paphiopedilum. In this first view none of the sexual

parts of the plant are visible. The stigma (the female part

of the plant which is the gateway to the ovary) is hidden

within the pouch at the back of the column (the central

extension of the stem and ovary that gives rise to the

anthers, stigma and staminode). The anthers (there are two

separate anthers in cypripedioids, unlike other genera which

only have one anther) are hidden behind the ears of the

staminode. The staminode is an interesting structure which

no doubt helps to attract the pollinator to the flower and

which provides part of the mechanical barrier that directs

the pollinator in the right direction to pick up and deposit

the pollen on the stigma.

|

Figure 1: Front view of

Paphiopedilum

|

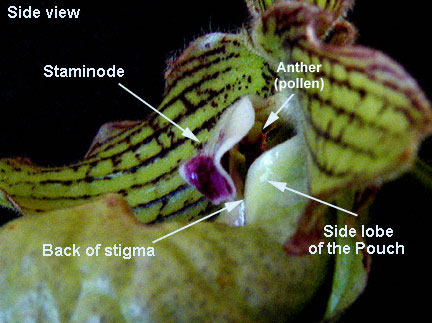

In Figure 2 we see a side image of an

intact flower. For the first time we can begin to see the

sexual parts of the flower. Behind the staminode we can just

see a bit of the anther. The majority of the stigma is

hidden behind the side lobe of the lip. We can just see the

back of the stigma where it attaches to the column.

|

Figure 2: Side view of

Paphiopedilum

|

In Figure 3 we have removed the pouch

where it connects to the column and view the flower from the

bottom. For the first time we can clearly see the stigma, a

broad, smooth, flattened fingertip-like structure. While it

is possible to pollinate a Paphiopedilum or

Phragmipedium without removing the pouch, it is

considerably easier to see what you are doing if the pouch

is removed. Generally an easy way to remove the pouch is to

rock it to one side until you hear a crack and then to the

other side. This should partially detach the pouch at each

side and the rest of the removal can easily be accomplished

with a bit of twisting and pulling. Be sure and support the

rest of the flower with your other hand so as not to damage

it during this process. Alternately, the pouch can be

removed by cutting with small scissors but if you choose

this route be sure and sterilize them so as not to risk

transmission of virus. There is no need to remove the

synsepal since it can generally be bent back out of the way

of the stigma (In Cypripedioideae the synsepal is formed by

fusion of the two lateral sepals and it forms a sort of

apron behind the pouch).

|

Figure 3:

Paphiopedilum with pouch

removed

|

|

Figure 4:

Paphiopedilum column

|

Once the pouch is removed the hard work is

really done. We will look at a few more views of the flower

just to provide a thorough orientation, but at this point we

have access to all of the structures we need to complete

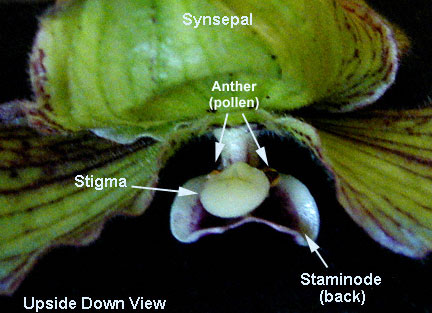

pollination. In Figure 4 we move in closer so as to

see the anther and the pollen on one side of the column

(remember that there is a second anther on the other side).

You can also see the relationship of the anthers to the

stigma and column in Figure 5. In this view we have

turned the flower upside down and are looking at it from the

front. The stigma can clearly be seen and the two anthers

can barely be seen on either side of the column behind the

stigma. The anther holds the pollen, which is attached via a

small horn or "hanger" off the column. In paphiopedilums,

the pollen is held in a waxy fairly undefined mass with the

consistency of mealy beeswax. It is difficult to distinguish

the anther cap (i.e. a cup-like structure that is well

developed in other genera that holds the pollen) in

paphiopedilums. At most, the anther cap in paphiopedilums

appears to be a slightly more consolidated waxy surface that

lies on the outermost region of the pollen mass. This

modification can best be seen in the fourth image as the

darker area of the pollen mass. While in most genera, the

pollen can easily be separated from the anther cap, this is

often difficult to accomplish in paphiopedilums.

|

Figure 5:

Paphiopedilum with pouch removed, looking

up

|

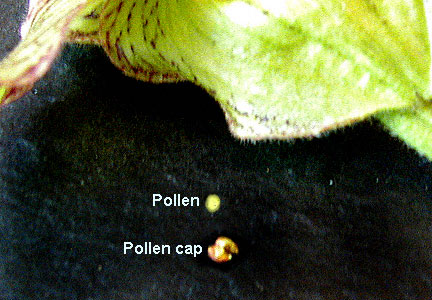

In Figure 6 we can see where the pollen

mass has been removed from one of the anthers and an attempt

has been made to separate the inner pollen mass from the

anther cap. The pollen mass can be removed by grasping it

with forceps or by sticking it to a toothpick. Since the

pollen mass is not particularly sticky, it may be necessary

to lick the toothpick or even to use the sharp end of the

toothpick to impale the pollen mass should you choose to use

a toothpick (for pollination). It probably is not necessary

to remove the inner pollen mass from the anther cap to

achieve pollination since both are soft and waxy and can

easily be smeared onto the stigma.

|

Figure 6:

Paphiopedilum pollen

|

In Figure 7 we can see where the inner

pollen mass has been applied to the stigma. This can be

accomplished by "sticking" the pollen mass to the stigma

using a bit of the saliva left on your toothpick or by

simply by pressing it up against the stigma surface using

gentle pressure from the toothpick. If the inner pollen mass

is not removed from the anther cap before applying to the

stigma surface, try to position the anther cap/pollen mass

so that the inner pollen mass surface is against the stigma.

The pollen masses from both sides should be used to maximize

the amount of seed obtained unless one of the pollen masses

is needed for other pollinations. The final step in

pollination is to the smear the pollen mass over the surface

of the stigma. This can best be accomplished with the flat

end of the toothpick. Gently push the pollen mass flat and

spread it over the surface of the stigma much like you would

butter a slice of bread. Be gentle so as not to gouge the

stigma or inadvertently break it off.

|

Figure 7: Pollen applied

to Stigma

|

|

Cross pollination is always preferable for

reasons of genetic diversity, but paphiopedilums

and phragmipediums can often be self pollinated

successfully if a suitable outcross is not

possible. The visible response to pollination in

paphiopedilums is minimal and often it is difficult

to tell if the pollination has taken until the

ovary begins to swell. Unlike many other genera,

the flower does not show any initial wilting in

response to pollination but abruptly falls off the

ovary leaving a clean scar at the ovary tip. The

ovary does not swell right away but if the stem

doesn't turn brown and desiccate it is likely that

your pollination has been successful.

The final image, Figure 8, shows a view

of the ovary several months following pollination.

Note the lack of the wilted flower at the apex of

the ovary, which is otherwise typically present in

orchids outside of this subfamily.

|

Figure 8: Developing

capsule of Paphiopedilum fowliei

Photo by Dale Borders

|

|