|

A Close Look at a

Brassolaeliocattleya

Text by Marianna Max and Photos by Dale

Borders

|

Figure 1:

Brassolaeliocattleya Drumbeat 'Heritage', a

showy hybrid

|

Pollinating an orchid is really quite simple

once you know the basic flower parts and where to find them.

Even relatively small-flowered orchids can be pollinated

using the following method although for this illustration we

will use a large specimen for clarity. The first

figure shows Brassolaeliocattleya Drumbeat

'Heritage' in full bloom. These large blooms make an

irresistible target for a pollinator (even though this is a

hybrid!). Large showy petals and sepals that flutter in the

breeze attract the pollinator's attention, in this case

possibly a bee. Flowers also have unseen (at least to us)

ways to guide pollinators to the target. For example,

flowers may have the equivalent of "landing lights" or

"runway guides" that are visible in the ultraviolet

spectrum. Bees, which can see in the ultraviolet, will see

very bright targets almost like a bulls-eye, but which to us

appear as simple striations. A flower like this may appear

very different to a bee than to us. As can be seen in

Figure 2, the striations in middle of the flower

point from the lip towards the center of the flower and the

column which houses the sexual parts of the flower. Let's

take a lesson from the bee and move in closer to take a look

at the structure of the column. A close front view of the

column can be seen in Figure 3.

|

Figure 2:

Labellum

|

|

Figure 3: Column as

viewed from the outside of the

flower

|

The column is the central structure that is

contiguous with the stem (pedicel) and the ovary. The petals

(usually held at 2, 6 and 10 o'clock with the petal at 6

o'clock being modified into a lip or in the case of

Cypripedium into a pouch) and the sepals (at 12, 4 and 8

o'clock) attach to the base of the column where it joins

with the ovary. The column contains the stigma, which is the

"female" sexual part of the flower and the anther, which is

the "male" sexual part of the flower. In most orchids the

anther is held at the front top part of the column. The

anther is made up of the anther cap, which protects the

pollen and sometimes positions a viscidium (sticky pad

attached to the pollinia via a thread or stipe) that helps

the pollen stick to the pollinator, the multiple locules

which hold the pollinia, and the pollinia, which consist of

pollen grains that are molded into hard and waxy or mealy,

solid, compact structures. Most orchids have two, four or

eight pollen masses or pollinia. No orchids have loose

pollen grains. Pollinators usually encounter the pollinia

when exploring the flower and these pollinia "glue"

themselves to the part of the pollinator which comes into

contact with them - either by being themselves sticky or via

a sticky viscidium, which attaches to the pollinia via the

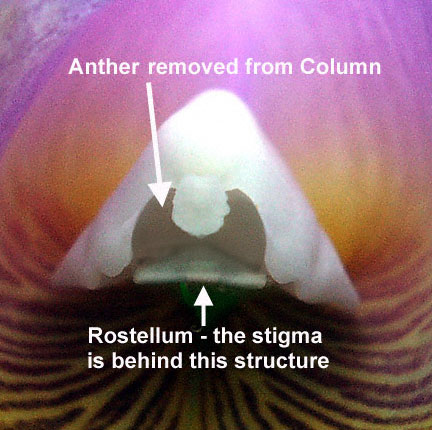

stipe. The rostellum is a veil-like structure that bisects

the column on a horizontal plane and is positioned between

the pollinia in their anther housing and the sticky surface

of the stigma. This can best be seen in Figure 4.

|

Figure 4: Underside of

the Column

|

The goal of this exercise is to get the

pollinia out of the anther and onto the sticky part of the

stigma without losing it on the floor! I like to place the

plant on a white piece of paper so that if I drop the anther

or pollinia, I will have a better chance of finding it. Using

the flat part of a toothpick, touch the end to the sticky

fluid on the stigma. You might want to remove the lip of the

flower the first time you do this so you can see what you

are doing, but generally this maneuver can be accomplished

"blind" by simply putting the end of the toothpick in the

vicinity of the stigma and briefly touching it. This will

make your toothpick sticky and make it easier to remove the

pollinia from the anther. Now, simply touch the toothpick to

the base of the anther cap and gently lift. This will expose

the pollinia and you can touch the pollinia with the sticky

part of the toothpick. Generally the pollinia will pull out

of the anther cap and either the cap will remain on the

column or it will fall away. Sometimes the whole assembly

will come away together. If that happens it is best to put

the anther in the dampened palm of your hand, and with the

toothpick in the other hand (hopefully still sticky), gently

touch the area where the pollen is located and pull up. This

should dislodge the pollinia from the anther cap.

Masdevallias are often difficult to pollinate because of

their small size and the fact that the pollinia tends to

stay in, and is difficult to remove, from the anther cap.

For these you may need a magnifying glass and forceps.

|

Figure 5: Anther cap and

Pollinia

|

Figure 5 shows a view of the anther

resting on a sepal of the flower. The pollinia have been

removed and are lying next to the anther. You can see the

locules (the sack like structures) that hold the pollinia.

Now it is a simple matter to pick up the pollinia with the

sticky stuff that is still on the tip of your toothpick. You

can simply make the same motion as you did previously when

you got the tip of the toothpick sticky. This time you will

carry the pollinia to the stigma. The pollinia should easily

stick onto the stigma surface. Figure 6 shows the

view that you will see as you bring the toothpick in towards

the stigma. Notice that the anther cap is gone and the

rostellum (the front edge of the stigma) is visible. If you

have removed the lip, you may want to view the flower from

the bottom. If you haven't removed the lip, it may be

necessary to gently push the lip down to get it out of the

way when you move the toothpick into position. Figure

7 shows the pollinia applied to the stigma. This is the

job completed! Now the rest is up to the flower.

|

Figure 6: Column end

after pollen removal

|

|

Figure 7: Underside of

Column after Pollination

|

What happens in the event of a "good"

pollination, i.e. one that is compatible with the plant, is

that usually the stigma swells and sometimes encases the

pollen. This response, which I call the pollination

response, indicates that the flower is aware of the

pollinia. This is a good sign but doesn't necessarily mean

that the pollination will be successful. Sometimes flowers

have mechanisms to avoid being self-pollinated and will not

complete the process if pollen from the same plant is placed

on the stigma. Often the flower will also wilt and some

flowers even change color upon pollination. Over the course

of the next few days, if the flower is responding

appropriately to the pollen, pollen tubes will form in the

stigma and grow into the ovary. These pollen tubes make a

passageway for the pollen grains to find the ovum and unite

the genome of the pollen with that of the ovum. In a "good"

pollination, the ovary will begin to swell, usually in a

matter of days. This varies amongst species but if you see

the ovary swelling, you are probably on your way to growing

a capsule. Even this doesn't guarantee success however, as

some flowers will grow a capsule and there won't be any live

embryos in the seed. This is the reason that Troy does a

microscopic exam of the seed that you donate. By performing

this operation he can estimate how many seeds have live

embryos and can estimate how many seeds to sow for the

mother flask. He can also avoid sowing seed with no live

embryos and this helps to make flasking cost effective.

Check out some of the seed reports here for a view of

embryos.

Bad Vanda

coerulea seeds Good

Vanda

coerulea seeds

Bad

Encyclia wendlandiana

seeds Good Encyclia

brachiata seeds

You can find out more about harvesting your

seed by referring to Troy's article "Capsule

Drying and Seed Preparation". There are also other

articles on this site discussing some of the unusual

pollinations required by certain genera, please check the

Index of Informational

Pages.

|